The Fate of Modern Office Buildings

Without a heritage listing, the preservation or demolition of an office building is up to the property owner. The deciding factor is whether the owner can see beyond an outdated mass of construction.

“Standing on the site brought up mixed feelings. The facade was in its original state and very closed off. It looked more like an indoor car park than a building where people would like to spend time.”

This is how a representative of a property development company described their first impressions of an office building designed by Aarne Ervi in Espoo’s Niittykumpu. The company had just acquired the 1971 building and was contemplating its future. Demolition was on the table as a viable option.

The owner has the right to decide on the fate of a building, unless the building is listed for protection in the local detailed plan or by law.

A great many modern office buildings from the 1960s and 1970s have been torn down in recent years. As regards the impact on the cityscape, they have been the most visible demolition targets, in addition to being the most significant in terms of the statistics. Renovating outdated offices is not considered to be worth the money and the effort, and the owners often prefer to simply replace the existing constructions with a shiny new building.

Preserving a building requires active decision-making. We will only repair what we deem to be worth preserving. For a building to be spared, the one making the call needs to identify a feature in the building that evokes the desire to preserve it.

For my master’s thesis last year, I interviewed property developers who had been involved in settling the fate of two 1970s office buildings. I wished to understand how property developers value industrially built office buildings, as well as the ways in which the values impact the decisions to either preserve or demolish them.

From Open-Plan Offices to Family Services

The office building at Niittyportti 4 in Espoo was completed in 1971 as the Kaleva insurance agency headquarters. In keeping with the times, the design followed strict financial discipline and a rationalist design philosophy. In Kaleva’s 1971 annual report, the building was described as a “non-monument”, a precast office building where all employees, including the managing director, sat in the same open-plan offices.

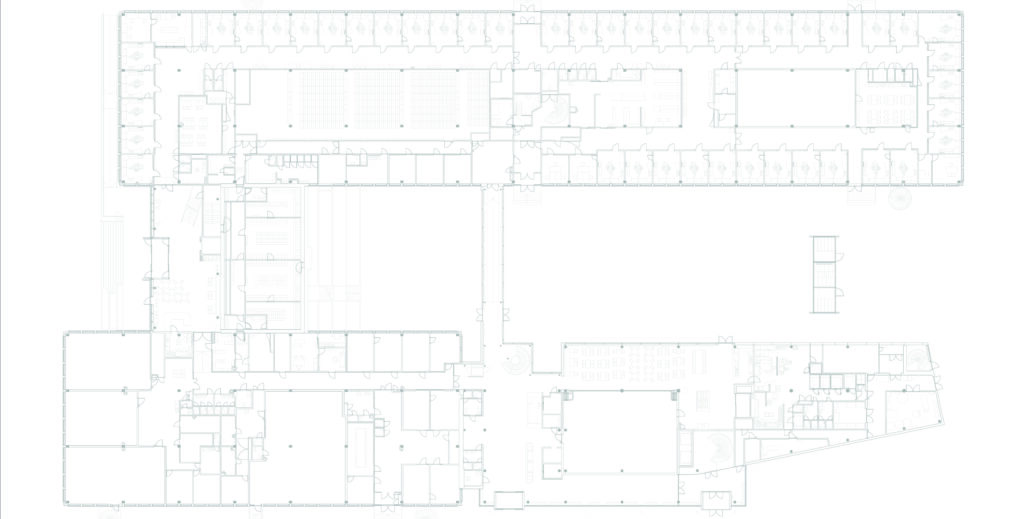

The building served as headquarters for various insurance companies up until 2020. When the last occupants moved out, the building was purchased by property investment and development company HGR Property Partners. The company implemented a comprehensive renovation of the building and gave it a completely new purpose. Now, the building is home to a family centre and dentists’ offices run by the Western Uusimaa Wellbeing Services County. The conversion was designed by PES-Architects, with Maritta Helineva as the principal designer.

From a Business Federation Building to Housing

The building at Mannerheimintie 76 in Helsinki was finished in 1979, originally serving as offices for the national retail and industrial trade unions. Later on, the building began to be known as the “Entrepreneur Building” after the national entrepreneurs’ federation that set up offices there. The construction of the office building caused an uproar in the 1970s because a well-known Art Nouveau building, commonly known as the “Church of Sipoo”, was torn down to make room for the new offices. In contemporary news headlines, the building was labelled in quite critical tones as a “concrete palace”.

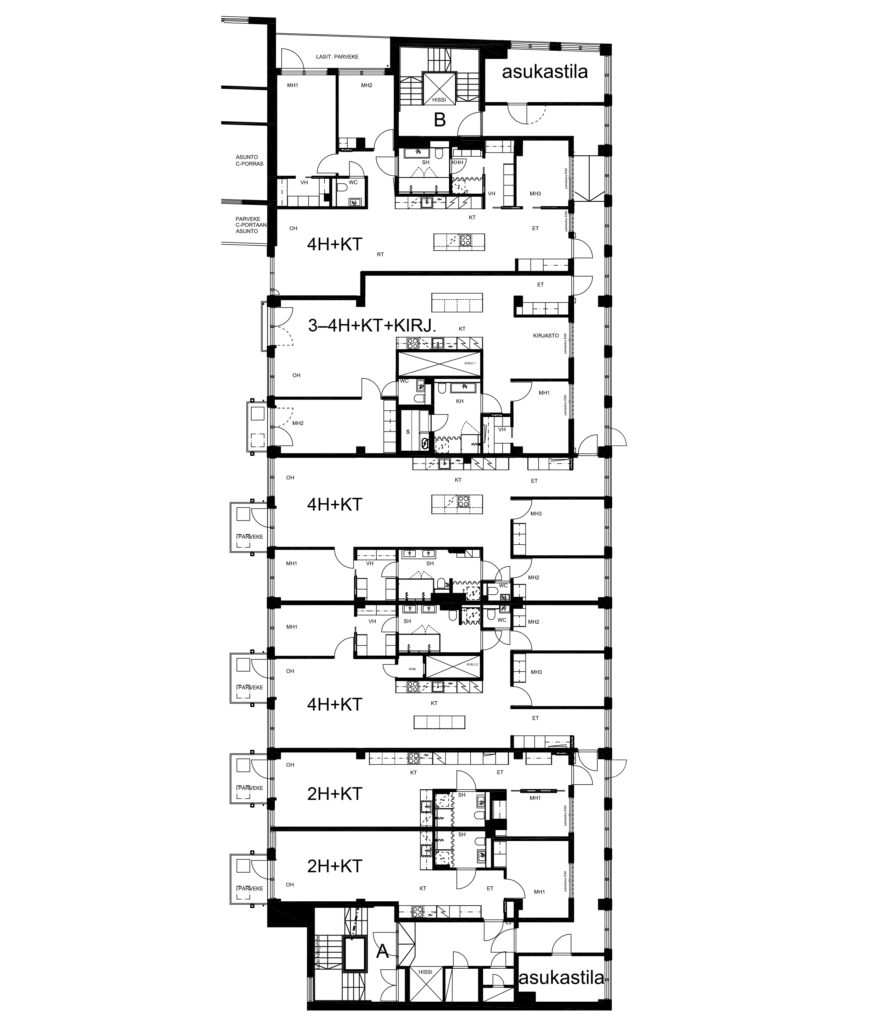

Once the Suomen Yrittäjät entrepreneurs’ federation moved out, the property was purchased by property developer Newil & Bau. Partnered with a handful of architects, the company explored the development of the site for housing. Some of the designers proposed a complete or partial demolition of the existing building. However, at the suggestion of architect Mika Penttinen, the developers ended up preserving the old building and converting it to housing. Architects Kirsi Korhonen and Mika Penttinen were placed in charge of the final designs.

Valuation Governed by Current Perspectives

In the initial stages of the two projects, demolition was a real possibility for both Niittyportti 4 and Mannerheimintie 76. If this had been about an early 20th century masonry building, I doubt anyone would have even brought up the option of demolition. Older period buildings are often automatically viewed as worthy of preservation. Their value is never in question, nor are they subjected to the same expectations as new construction, as described by the developer for Niittyportti 4:

“People have learnt to appreciate old Art Nouveau buildings and similar period architecture. Even with their awkward room sizes and other shortcomings, they are regarded as such magnificent buildings that people want to work in them and are prepared to tolerate the suboptimal conditions.”

With modern buildings, the views are much more unforgiving. They are expected to meet current standards and aesthetic ideals. This places them in a problematic competitive position in relation to new construction. If an older modern office building cannot meet the expectations placed upon it, it can automatically be deemed outdated and replaced with a new one.

The decision to preserve a building is not always up to the properties of the building itself, but rather a will to tackle any challenges.

Life Cycle as a Relative Concept

From today’s perspective, outdated buildings do not always attract office tenants. Their preservation, then, can require the complete repurposing of the building, which ended up being the case with both Niittyportti 4 and Mannerheimintie 76.

For Niittyportti 4, preservation was supported by the fact that plenty of new uses were identified for the building and the floor plan was easy to divide into sections for rent.

The issues having to do with repurposing can be complex, and cut-and-dried solutions are not always readily available. This was also the case with Mannerheimintie 76. The project had to solve several technical problems in order for the building to comply with current housing standards. According to the developer’s representative, among the difficulties were the low ceiling height and the implementation of proper ventilation. The deep frame also caused challenges due to the requirement that the homes facing Mannerheimintie also had to have windows facing another direction.

The problems were very real, but, in the end, solutions were found for each one. The decision to preserve a building is not always up to the properties of the building itself, but rather a will to tackle any challenges. It is often easier to label a building as being poorly designed and declare that it has reached the end of its life than to take on the task of exploring potential new uses.

The demolition of modern-era office buildings is frequently justified with exactly the argument that they have reached the end of their life cycle. The claim is not completely unfounded, as design in the 1960s and 1970s emphasised short-term needs and the ageing of the buildings was not always considered at the baseline. Many of the buildings are now in need of extensive and expensive repairs.

Still, labelling a building as unfixable is, in many cases, a value choice and not merely a technical fact or a matter of economics.

Labelling a building as unfixable is, in many cases, a value choice and not merely a technical fact or a matter of economics.

The Despised Era

A significant reason behind the tearing down of modern buildings from the 1960s and 1970s is that people do not really appreciate them. The architecture of the time was already criticized in contemporary discussions for offering a “one-dimensional experience”. This critique has then become the predominant interpretation of the construction from that period.

Today, the buildings are often viewed as dull and stark. The developer of Niittyportti 4 described the look of the facade as follows:

“The worn-out facade had not seen any investments in the last 50 years. Even the original colour had turned into something completely different. The window louvres gave the building a bleak, closed-off and gloomy appearance.”

Modern architecture is subject to an expectation of newness and being in good condition. Any wear and tear is interpreted as a flaw and a lack of appreciation, not as valuable patina. This was also palpable in the developer’s views on Mannerheimintie 76:

“There were neon signs and other traces of use. I have to say that it was not pretty. Still, we were able to see the building for what it could become.”

The new owners of Niittyportti 4 and Mannerheimintie 76 saw aesthetic features that were worthy of preservation in the properties despite their worn-out overall image.

In the case of Niittyportti 4, the crucial turning point was when the developer was able to tour the inside of the building and saw that the spaces were in surprisingly good condition. The clean surface materials, the natural light that filtered in through the skylights and the clear floor plan quickly changed the developer’s reservations into a positive impression.

The owners also recognized the value of the architect who had designed the building:

“You could see Ervi’s architecture shine through. Even though the building is not listed for protection, we wanted to respect it and find the right solutions to preserve it.”

With Mannerheimintie 76, the materiality and spatial quality of the building also supported the decision to preserve the building:

“The 70s concrete architecture was extremely fascinating. Concrete is a fine material, very systematic. The building had large entrance halls and a lot of great elements.”

In the end, aesthetic value is not just an external feature of a building but an interpretation that can also change. When the appearance, materials and history of a building begin to take on a meaningful relevance in the eyes of the decision-maker, the fate of the building can be resolved in unforeseen ways.

Preservation as an Ideological Issue

The preservation of both Niittyportti 4 and Mannerheimintie 76 was, first and foremost, rooted in the values and the willingness of the property owners to seek alternatives to demolition.

These two cases introduce an important perspective to the current discussion on demolition versus preservation. Decisions to preserve would be feasible far more often than is currently the case, if developers were able to see the buildings both for the material resources bound in them and as the carriers of immaterial meanings.

Here is where an architect can impact the end result. By bringing the hidden potential of an existing building into the discussion, we can invite those who decide on the fate of the building to look beyond the surface. A worn facade can reveal a highly significant deeper whole.

Ultimately, everything hinges on whether the property owner sees something in the building that is worth preserving. In the best case scenario, this results in a solution that is ecologically more sustainable, in addition to having a more interesting identity than a new building.

Therefore, it would be important to have architects with relevant expertise and the best vision as to the potential of a building involved in the decision-making concerning preservation and demolition. ↙

HELMI HÄKKINEN is an architect, whose master’s thesis Arkipäiväisen arvo (“The Value of the Everyday”) examined office building architecture from the 1960s and 1970s. The thesis was approved in the autumn of 2024 at Aalto University.