The Fifty-Year Myth

An often-repeated claim in the media and popular discussions is that 1970s buildings were not designed to last for more than thirty or fifty years. Where did this belief come from? Might there be some truth to it?

“We are now faced with deciding on the fate of buildings constructed between 1970 and 1999. They were originally designed to last for 50 years. The quality of construction during this period was not very high. – – The oldest among the buildings in this age group are now running out of time.”

This quote is from the Helsingin Sanomat newspaper editorial from last April, but it could have been published in just about any other paper in Finland.

The notion that 1970s buildings were only designed to last for fifty, or even as little as thirty, years is repeated at regular intervals in the media and in people’s comments. It has become a generally accepted fact of a sort that can be thrown around whenever people feel the need to justify the demolition of a building that they do not deem worth saving.

As design professionals, however, architects are rarely willing to subscribe to this view.

“It is absolute humbug”, says Professor of Sustainable Renovation Satu Huuhka from Tampere University. She is in charge of the international ReCreate project that is investigating the sustainability of recovered precast concrete panels and their applicability to repurposing and reuse. The results have been promising.

“Measured on the international scale, 1970s buildings in Finland are good-quality constructions and highly repairable.”

Where, then, does this pervasive and deeply instilled myth about the short service life come from? This is something that Huuhka is unable to explain, but she points us to her colleague, Research Manager Jukka Lahdensivu at the Tampere University Department of Civil Engineering, who might know the answer.

“Measured on the international scale, 1970s buildings in Finland are good-quality constructions and highly repairable.”

Average Lifespan of 150 Years

It turns out that Jukka Lahdensivu has a lot to say about both the service life planning of buildings and about how precast concrete buildings from the 1970s have actually stood the test of time.

In addition to his professorship, he works as a Managing Consultant at Ramboll.

Lahdensivu’s 2012 doctoral dissertation was entitled Durability Properties and Actual Deterioration of Finnish Concrete Facades and Balconies, so he is well-informed on the topic. During his doctoral research, he also familiarized himself with the guidelines drawn up as regards durability aspects in the 1960s–1990s.

Lahdensivu, too, has often come across the claim that 1970s buildings were not built to last for more than a few decades. According to his own research, however, the claim is not factual.

“None of the published guidelines support such a statement. There is simply no technical evidence to back this claim”, Lahdensivu explains.

In fact, he points out that service life planning was not even adopted in Finland until the early 2000s. Moreover, service life planning does not mean that buildings are only designed to last for a predetermined period of time.

“The premise is that 95 percent of the structures exceed the targeted service life and that only five percent do not reach it without any damage. In reality, the average durability of structures designed for a service life of fifty years is actually some 150 years.”

The service life calculation norm for concrete structures was created in 2004 and the one for steel construction shortly after that.

“I don’t think we even have one for wood constructions yet, let alone for masonry or rendered structures.”

“So, if someone claims that buildings constructed in the 70s were designed for a specific service life in mind, they simply don’t know what they are talking about”, Lahdensivu concludes.

After all, there are usually no issues in structures that are located in a warm and dry space, as Lahdensivu points out. In such conditions, any material will last forever. But when a structure is exposed to weather conditions or, say, chemical stress, the designers have to pay more attention to the matter of durability.

“The indoor section of a load-bearing frame typically lasts with no issues. If you redo the facades and windows, the building is like new again.”

Remarkably Well Preserved

In the 1960s and 1970s, durability was not an area that received much consideration, at least not in the concrete industry. Jukka Lahdensivu reflects that this may be one of the reasons why the durability of the era’s building stock has been so underrated in popular discussions.

Though it must be said that it was not exactly a priority before the 1970s, either. Still, this does not mean that the buildings were not built well or meant to last.

“The matter of air entraining to make concrete endure our outdoor conditions did not enter the discussion until 1976, and the related industry standards were not adopted until 1980.”

In air entraining, an admixture is added to the concrete mix in order to increase the amount of air within the concrete. When water that has permeated the concrete freezes, it has room to expand into the tiny air pockets, thus protecting the concrete from damage.

Significant measures to improve the durability of concrete structures were not introduced into planning and implementation until the early 1990s.

What Lahdensivu finds noteworthy is that the 1970s structures have actually withstood the test of time remarkably well, despite the seemingly poor baseline durability properties. This is because the actual weather conditions are never as severe as what our design standards seek to prepare for.

“And, of course, anything can be repaired, as long as the repairs are made early enough.”

The reasoning behind demolition is typically not the condition or poor durability properties of the building itself – instead, the root of the matter has to do with financial considerations.

New Construction as the Root Cause

The only potential source where Jukka Lahdensivu has come across the idea that buildings constructed in the 1970s were not designed to last for more than a few decades has been an interview with former President of Finland Mauno Koivisto dating back to the 1990s.

In the interview, President Koivisto was reminiscing about his career as General Manager of the Helsinki Workers’ Savings Bank in the 1960s, when the bank was involved in financing large urban development projects.

“President Koivisto recounted that the general mindset, as developers were setting up entire new suburban districts, was that, in another thirty years, the overall standard of living in Finland would be so high that everyone would be able to afford a house of their own and the suburbs of multistorey apartment buildings could all be torn down.”

“My guess would be that this notion, expressed by Koivisto, is what lies behind the thirty-year myth. It is not really based on the technical properties of the buildings, but rather on the perspective of the economy.”

Indeed, according to Jukka Lahdensivu, the reasoning behind demolition is typically not the condition or poor durability properties of the building itself, and, instead, the root of the matter in the majority of cases has to do with financial considerations.

“New detailed plans extend the scope of development rights or allocate more valuable real-estate to existing properties, which leads to the demolition of old buildings to clear the way for the new moneymakers. The decision to demolish can, of course, be ostensibly based on a variety of justifications, but the root cause is to make room for new construction.”

This is also evident in the fact that more buildings are torn down in Helsinki than in any other part of the country – which is to say precisely where there is also the most new construction.

A Wide-Spread Myth

Where Jukka Lahdensivu is well-versed in the durability of precast concrete buildings from a technical perspective, architect Niko Kotkavuo approaches the topic through archive sources.

Kotkavuo is preparing his doctoral dissertation in architecture at Tampere University, studying the history of precast concrete construction and precast concrete systems in Finland. He has also often come across the claim that 1970s buildings were not built to last for more than a few decades.

As regards the validity of such a claim, Kotkavuo concurs with Satu Huuhka and Jukka Lahdensivu.

“It is a myth.”

Niko Kotkavuo has noticed that, back in the 1990s, people were still referring to a service life of thirty years but that the number has since gone up to fifty. He suspects that this jump is due to the adoption of service life planning in Finland in the early 2000s. A typical category in service life planning is fifty years.

Kotkavuo says that the perception of the short-by-design service life of 1970s building stock can also be found in research literature. The final report (2012) of the Entelkor project on energy-efficient suburban renovations by the then Tampere University of Technology states that the Finnish apartment buildings from the 1960s and 1970s were originally planned to be used for only 30 years.

The source citation for this statement leads to a doctoral dissertation by architect Johanna Hankonen, a classic study on suburban development and the pursuit of efficiency, entitled Lähiöt ja tehokkuuden yhteiskunta (1994). Among the themes discussed in the dissertation is the culture of disposability that gained ground in the 1970s, the impacts of which were also felt in construction.

Niko Kotkavuo points out, however, that Hankonen never makes the claim in her dissertation that the apartment buildings of the 1960s and 1970s would have been specifically designed to last for a mere thirty years.

“The theme is alluded to, yes, and this is one potential source where such a claim may have sprung from. But nowhere in her dissertation does Hankonen actually spell it out in so many words.”

What Kotkavuo finds of particular interest is that, in a different work published a year after her dissertation, Hankonen makes a point of emphasising that she has not familiarized herself with the actual building practices applied on construction sites and precast concrete manufacturing plants.

Economic and Technical Service Life

Niko Kotkavuo has also reflected on the passive voice that is so often used in connection with the thirty- or fifty-year claim. If buildings “were designed” to last for just a few decades, who, exactly, were the ones making such design choices?

“I can tell you it wasn’t the architects or structural engineers. But it might have been a consideration at some higher level of housing administration.”

In her dissertation, Johanna Hankonen cites a survey on the economic service life of apartment buildings by Seppo Suokko, entitled Asuinkerrostalojen taloudellinen käyttöikä (“The Economic Service Life of Apartment Buildings”), published in 1970 by the then VTL Institute of Technological Research (currently VTT).

The report entails separate examinations of the technical and economic service lives of buildings, with the main conclusion that the two are not mutually compatible, as summarised by Kotkavuo.

This is based on the common presumption during that period that the economy would continue to grow, and the cost of construction would come down due to the shift towards precast construction, while the value of land would go up.

“The view at that point in time was that, if these trends were to continue, the chasm between the technical and economic service life of a building would become even wider. One of the main conclusions of Suokko’s study is that there is no point in modernising old apartment buildings, and developers should just tear them down and build new ones.”

Suokko’s report was written before the 1973 oil crisis that raised energy prices and thereby also the costs of construction, and way before the current climate and environmental discussion. If we are to curb emissions, current knowledge suggests that it almost invariably makes more sense to renovate than to tear down and replace an existing building with a new one.

The 1970s structures have actually withstood the test of time remarkably well, despite the seemingly poor baseline durability properties.

Highlighting the Cost

Even though Niko Kotkavuo also could not find any indications that buildings would have actually been designed to last for only a few decades, he does admit to understanding where this type of thinking is coming from.

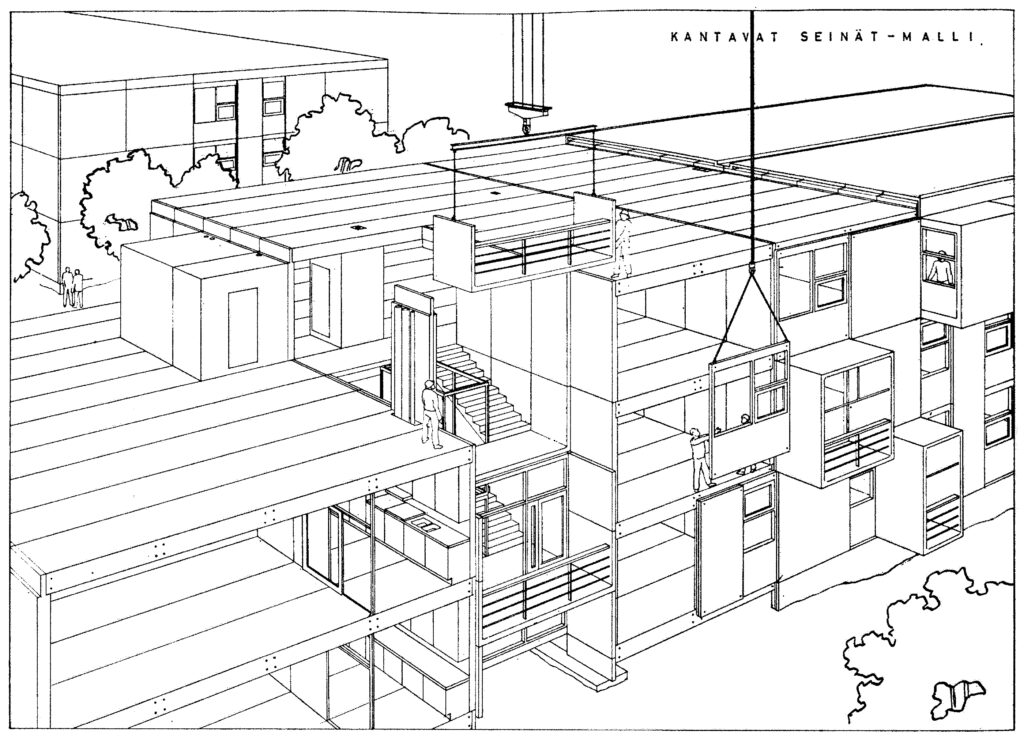

While the standardized precast concrete system for housing production, BES, was being created in the late 1960s, there was immense pressure towards a rapid increase in housing production, particularly in large growth centres. The system was developed with the cost of construction as the leading criterion.

“The mindset at the time was that we either build a lot of homes cheaply or just accept a high housing shortage.”

One of the pros of BES was that, when the entire construction industry was using the same standardized precast units, the production facilities did not need to customize their products according to the needs of specific developers. The units could be purchased from any factory, which sped up construction significantly.

At the development stage of the BES system, loftier objectives were also entertained, such as the so-called relocatability. The idea was that should a building no longer be needed at its original site, it could be taken apart and moved to another location.

“The nobler goals were lost somewhere along the way, but the BES system was, by no means, designed with disposable buildings and a service life of only thirty or fifty years in mind”, Kotkavuo attests.

The Same Basic Principle

The claim that was made in the Helsingin Sanomat editorial about buildings constructed between 1970 and 1999 reaching the end of their life is based on the Rakennettu Suomi 2025 (“Built Finland 2025”) report that was published by the WSP consulting firm in early April of this year.

The report discusses the Finnish building stock from 1940–1999 and the locations in which our modern built heritage is at the greatest peril of being torn down, in addition to analysing the factors that should be considered when making demolition decisions.

The report highlights perspectives that are in favour of the preservation and renovation of our modern building stock, as well as emphasizes the significance of reusing building components.

On the other hand, the report also states the following:

“The renovation of 1970s and 1980s buildings is challenged by their many damage-prone structures and poor structural quality. The buildings from this period were originally designed for a service life of 50 years.”

“Water does not permeate concrete to the degree that people seem to think, and the structure is also able to dry outwards.”

Jukka Lahdensivu disagrees with the WSP report when it comes to the high prevalence of risky structures and the poor structural quality.

“As regards precast concrete structures, the new units manufactured today are exactly the same as those made in the 1970s. We now have slightly higher numbers of insulated wall panels, the strength of the concrete is somewhat higher, the rebars are slightly different, but the physical functional principle is exactly the same”, says Lahdensivu.

The topics studied by Lahdensivu include moisture damage occurring in the glass wool that was used as insulation in 1970s buildings.

“My dissertation entailed more than two thousand moisture measurements, and the fact is that the wool is as dry as dust. Water does not permeate concrete to the degree that people seem to think, and the structure is also able to dry outwards. As such, the claim that precast concrete is a risky structure is not accurate.”

According to the WSP report, generally recognized structural issues in public and commercial buildings constructed between 1940 and 1999 include the quality of concrete structures in the external envelope, as well as damp basements and moisture-proofing deficiencies in flat roof structures.

Lahdensivu states that elevated moisture concentrations can, indeed, be detected in basement structures that are in contact with the ground, if the waterproofing has not been sufficient.

“But these issues are also fixable. And as for flat roofs, studies have revealed that they are the least likely to have water damage.”

“As for flat roofs, studies have revealed that they are the least likely to have water damage.”

“I believe that the bad reputation of flat roofs is rooted in the 1970s flat roof boom in detached houses and in poor-quality rag felts, as well as the fact that the homeowners used to build the roofs themselves. But research does not support the claim that flat roofs in themselves are a problem.”

The WSP report further suggests that, in addition to damage-prone structures, the repairability of buildings from 1940–1999 is challenged by climate change, stating that the facade structures are not designed to endure the increased moisture burden.

This is absolutely true, says Lahdensivu, but only in the purely semantic sense, as the facades were not specifically designed for any particular level of moisture burden.

“This is another topic that we have studied on the Hervanta campus in Tampere. You can familiarize yourself with the research in, for instance, Toni Pakkala’s dissertation. When it comes to the risks caused by climate change in terms of rebar corrosion or concrete erosion, for example, our current engineering standards are quite sufficient to meet the future demands of the climate.”

According to Lahdensivu, the overheating of homes is going to be a more serious challenge brought on by climate change than the moisture burden on buildings. It is also not something that only affects buildings from the 1970s, but rather covers the entire Finnish building stock constructed to date.

The Last Resort

The WSP report does not contain source citations or a list of references that would allow the reader to check the origin of the statements made.

One of the authors is Unit Manager of Renovation and Refurbishment at WSP Finland, Master of Science in Civil Engineering Susanna Ahola. She explains that the data cited in the report regarding the structures are based on a building inspection and renovation guide for buildings with microbial damage, as well as building inspection guides for concrete facades, among other sources. In addition, the authors have utilized the Kerrostalot (“Apartment Buildings”) book series that introduces the typical structures used in apartment buildings constructed during different decades.

“The aim was to compile a report that offers something for everyone, with all of Finland in mind, and the report may not meet all of the criteria for a research article”, Ahola explains.

She admits that the claim concerning the designing of 1970s buildings to only last for fifty years is a sort of “common mantra”. She feels that it is particularly associated with the durability of 1970s facade structures.

“During the peak of suburban development, the field was yet to receive durability planning guidelines for concrete structures that are exposed to weather conditions. Perhaps the thought process was that the suburbs could not possibly last for very long because the quality of the concrete manufactured in those days was much lower. Even if studies have subsequently shown that the buildings have actually lasted quite well, all things considered.”

Ahola suspects that this view may have also been influenced by the major shift in construction that occurred during the 1970s.

“Back in the 1940s and 50s, when materials were scarce and builders would recover anything and everything, utilizing existing materials and components, but the 1970s was an era of a hard-line linear economy, preferring brand-new materials and the production of new things. Now, we have once again reverted to talking about the fact that we should be using what we already have.”

This is, according to Ahola, also the core message of the WSP report. Old precast concrete buildings have an abundance of elements and components that have remained in good condition and would be excellent candidates for reuse.

“It’s just that many of the buildings happen to stand in the wrong location in relation to where today’s people and the jobs are. We are well-stocked in existing building materials, as it were, but they are just not being put to optimal use.”

Susanna Ahola is saddened to hear that the WSP report can also be interpreted as an encouragement to demolish 1970s buildings, saying that it was certainly not the intention.

“No building should be condemned to be torn down just because it was built during a specific era. The point of the report is to introduce a regional examination of the particular areas to which investments should be allocated when money for repairs is scarce.”

“We would especially like to encourage people to renovate and to promote the reuse of building components. A decision to demolish should always be a last-resort solution”, says Ahola.

She relates that the report was not commissioned by an external client but that it was drawn up as part of WSP’s own publication activities.

“It’s just that many of the buildings happen to stand in the wrong location in relation to where today’s people and the jobs are.”

It’s All About the Money

It would appear that there is no historical evidence to back the claim that “1970s buildings were originally designed to last for only fifty years”, at least if we approach the issue from a purely technical perspective.

Perhaps the economic views of the era and the pursuit of optimal cost-efficiency in construction – and, on the other hand, the commonly held disdain for the aesthetics of suburban concrete architecture – has just been twisted over the decades into a belief about the poor quality and downright unrepairability of precast concrete buildings from the 1970s.

The economic mindset of fifty years past is, in many respects, still alive and well. We have yet to move away from a linear towards a circular economy, and building from scratch is still often considered to be financially more sensible than renovating an old building, regardless of whether this view is backed up by a proper cost comparison.

It would be more honest to admit this out loud instead of going on and on about buildings that have “reached the end of their technical service life”. ↙