The Unknown Side of Eliel and Eero Saarinen

Jari and Sirkkaliisa Jetsonen's new book presents residential buildings designed by the Saarinens, many of which have previously been overshadowed by impressive public buildings.

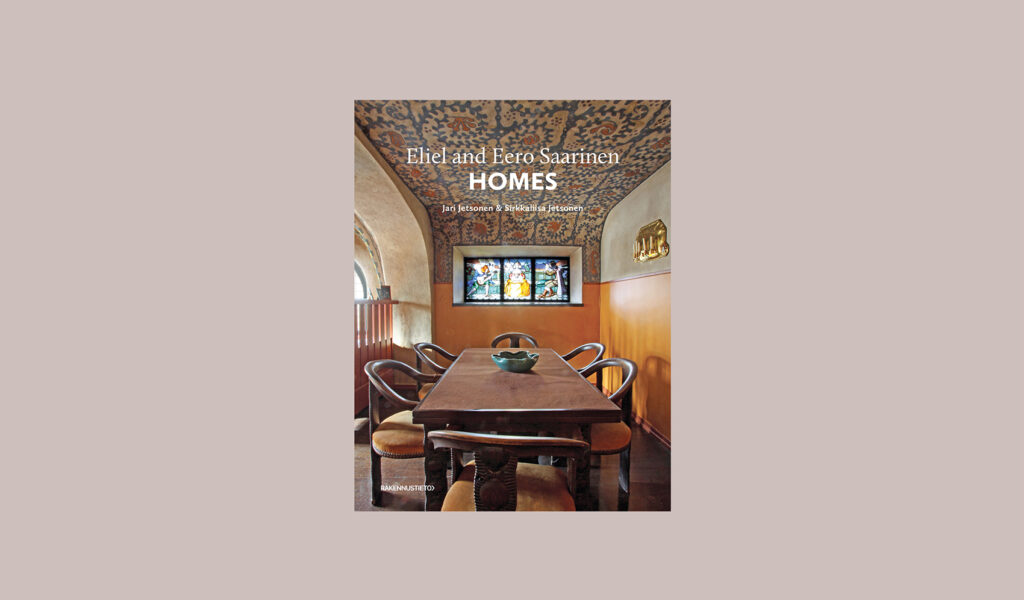

Jari Jetsonen & Sirkkaliisa Jetsonen: Eliel and Eero Saarinen Homes. Rakennustieto 2025. 282 pages.

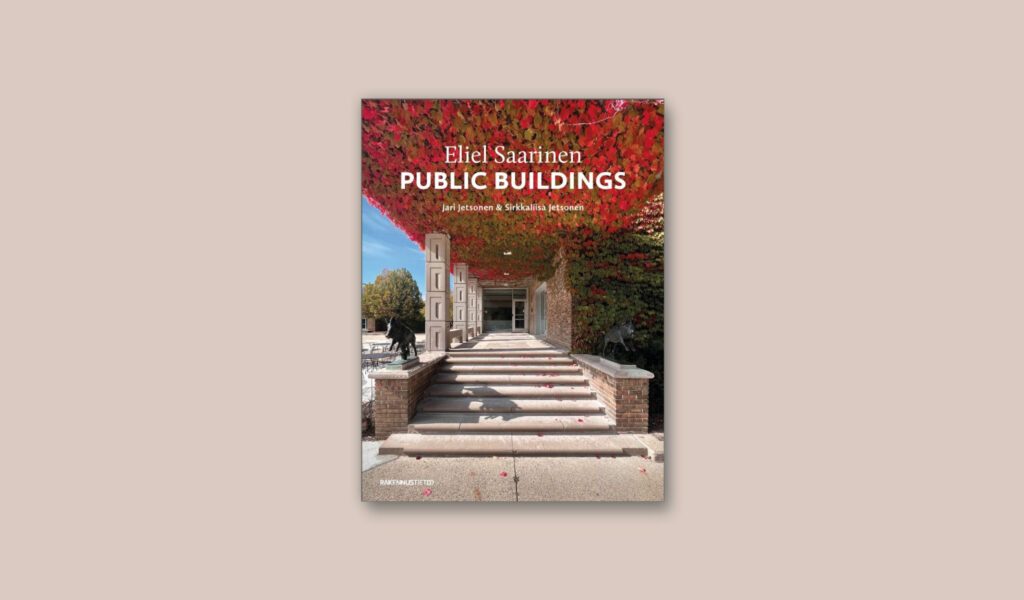

Jari and Sirkkaliisa Jetsonen’s hefty book Eliel and Eero Saarinen Homes continues the book series that began with Eliel Saarinen Public Buildings published last year now featuring housing and private houses designed by Eliel and Eero Saarinen. The English-language coffee table book is presumably targeted also at an international audience in order to spread the good word about Finnish – and American – architecture.

Sirkkaliisa Jetsonen’s text is uncluttered and even beautiful. The authors’ viewpoint emphasises the life lived in the residential buildings rather than style-historical analyses, and the images allow the reader to enter the spaces. Instead of a history book, the approach – images, texts, layout – resembles the site presentations in current editions of the Finnish Architectural Review. The reading experience is like time travel: a 60-year timespan glimpsed through modern presentation techniques.

The special merit of the book is that it takes the reader into private places. In addition to well-known apartment buildings, the Jetsonens have been able to photograph many lesser-known wooden buildings, for example the villa on Mäntyharju (1901) designed by Eliel Saarinen for his parents. Obtaining permission to photograph the buildings must have involved a great deal of sometimes thankless work, which is easily forgotten by the reader: not everyone wants their homes to be published. For example, the finest panelled dining rooms of the Tampere Savings Bank (1903) and the apartment building at Fabianinkatu 17 (1901) in Helsinki are not seen in the book, but the list of buildings visited is still respectable, and there is no shortage of important sites.

The latter part of the book, which will be less familiar to Finns, illustrates the transition from the father Saarinen’s work in the United States to intergenerational collaboration and finally to Eero Saarinen’s own housing design. This part of the younger Saarinen’s work has previously been overshadowed by his stunning public buildings.

The living room of the residence hall designed for female students at Vassar College features a recessed seating area typical of houses designed by Saarinen. Photo: Jari Jetsonen

Many of the book’s images and even some of the texts were previously used in the Jetsonens’ book Saarinen Houses, published by Princeton Architectural Press in 2014. The time span of the two books has made it possible, for example, to photograph Villa Winter in Sortavala (1912) before the Russian blockade and to photograph some of the sites without furniture, for example between changes in occupancy. The lack of furniture often brings out the architecture better. However, those who have read the Saarinen Houses book should be prepared for repetition, and it would have been polite to have informed the reader about this. According to Sirkkaliisa Jetsonen, the new book is a totality of its own, as it now presents not only private houses but also apartment buildings.

In Jari Jetsonen’s photos, the homes are repeatedly shown as spaces that are lived in: there is a playfulness in the photo angles, which cleverly counteracts repetition in a book covering numerous sites. The change of seasons adds a richness to the presentation. A few images reproduced from the previous book are annoyingly blurred, and in some cases the effects of an image-processing software are too obvious. But the majority of the photographs are impeccable. They are supported by illustrative drawings and historical photographs.

The reading experience is like time travel: a 60-year timespan glimpsed through modern presentation techniques.

The main emphasis is on the preserved sites. Among the demolished villas, the extensively studied Suur-Merijoki (1904) and Haus Remer (1907) are included. In the presentation of these, black and white photographs colourised by Jari Jetsonen have questionably been used. The photographs never reproduce reality as it is, and they always include the interpretation of the photographer and the person processing the image, but I am wary of interpreting lost colour impressions after the fact. At the very least, the post-colourisation should have been mentioned in the picture captions, not just in the references at the end. Fortunately, most of the archive photographs have been left in black and white. The original autochrome colour series of Suur-Merijoki by its owner Max Neuscheller could have been used. A more in-depth analysis of the early demolished Träskända (1901) and Paloniemi (1900) manors by Gesellius, Lindgren & Saarinen is left to future researchers.

Finally, an observation about the title of the book: including the names of four architects on the cover would have been cumbersome, but I cannot help but think that once again Herman Gesellius and Armas Lindgren are left in the shadow of the master’s name. Almost half of the buildings in the book are joint works by the partnership of Gesellius, Lindgren & Saarinen, the creations of three equal architects. Perhaps one day we will get a commemorative book, featuring all three and not just one. The focus in architectural narratives on a single master still holds firm. ↙