Updating the Toolbox

Established by Markus Wikar and Toni Österlund in 2015, Geometria Architecture is an architectural practice based in Helsinki and Tampere. In addition to their own design projects, the firm also assists other designers in the utilisation of digital technologies and the implementation of more complex projects.

Markus Wikar and Toni Österlund – your projects highlight unique shapes and structures conceived through digital processes. What are your thoughts on the concept of craftsmanship in contemporary architecture and design?

Digital design and computerised processing have become an inevitable part of the craft and toolbox of the modern-day artisan – irrespective of the specific field. Knowing and being able to use the available tools is important, just as it has always been in the more traditional crafts.

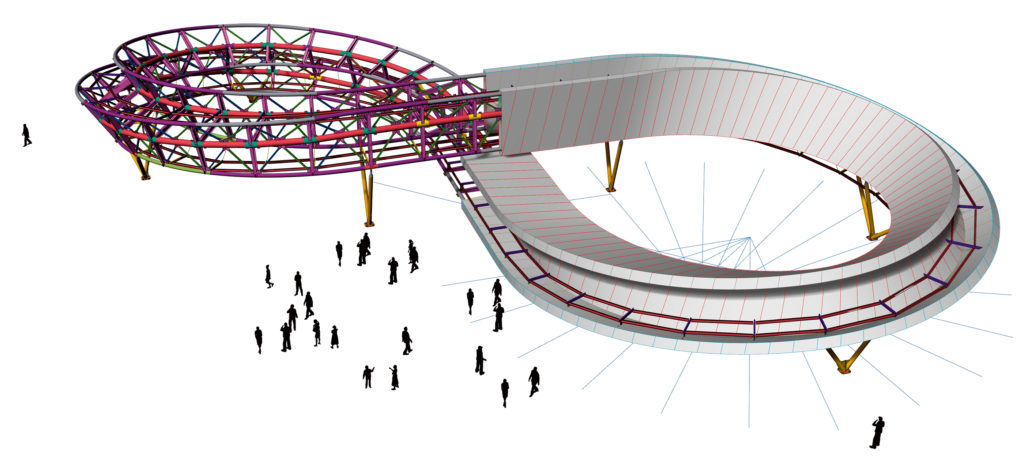

But instead of resigning ourselves to simply emulating the old ways with an updated toolbox, we seek to develop solutions that make full use of the new possibilities brought along by digital design and fabrication. For a designer, this calls for an ability to grasp and manage the entire set of tools available from the geometry of shapes to utilising the capacity of a machine tool. This is called digital craftsmanship.

Algorithm-aided design enables multiform construction that is based on repetition and variation. The accuracy and the endless capacity for variation in individual building elements that come with a digital design and fabrication process free the designer from conforming to rigid catalogue solutions.

Several of your projects have utilised wood, which is often associated with a traditional method of construction. How important are the materials to you?

We like to design for different materials. It is important to us to be able to collaborate with partners who have expertise in the material we are working with in our designs for buildings or structures – whether it be wood, steel or concrete, for example. A design team that combines knowledge of the material, structural joint design and algorithm-aided shape generation and fabrication is well-equipped to produce a successful end result.

In Finland, wood is readily available, and solutions for the versatile processing of the material have been widely adopted in low-rise residential construction and larger projects alike. Wood is an easy material to process and manage, and it is also quite forgiving in many respects. Several of our projects have utilised simple timber joints that rely on the tradition of timber construction, offering a capacity for variation that lends itself to multiform and cost-effective architecture.

Can a machine-fabricated end result be evaluated in the same way as traditional craftsmanship or building by hand?

You can look at and define this matter from several perspectives . What constitutes a machine-fabricated end result versus traditional craftsmanship, and what sets it apart from building by hand? Does a machine-fabricated end result refer to something that is digitally designed, processed with a digitally operated machine tool, or assembled by industrial robots? Is there a relevant difference between an egg-shaped structure designed with algorithm-aided software and a traditional-style log cabin, if both have been designed on a computer, processed with the same machine tool and assembled manually on site, and if both have been built by utilising timber structures developed centuries ago?

Digitality and modern wood processing techniques are already so deeply rooted in everything we do that the concept of “hand-built” can entail a wide range of varied methods. The tools applied do not define the end results, they simply render it possible to make. A “machine-built” end result may be recognisable as a specific type of architecture in terms of the materials and joints, but the building still settles into a continuum of building practices, even if it does open up some new perspectives on what a building made from wood, for instance, can be.

What are the impressions and attitudes often associated with parametric design or algorithms in the sphere of architecture? Have they changed?

Our own history in algorithm-aided design spans over a decade now. During this time, a clear path has emerged from experimental multiform design in architecture through the automatisation of the fields of engineering to the rationalisation of construction and production. As new avenues are opened, architects are naturally keen to utilise them, and particularly during the early stages in the development of the new design methods, this created a false image of algorithm-aided work inevitably leading to a distinctly organic design language. The benefits of algorithm-aided design are admittedly emphasised in multiform structures, but this does not detract from its utility in other areas. Utilising algorithms does not replace anything but broadens the possibilities.

Our current experience shows that, from the point of view of a contractor and developer, for example, algorithm-aided design streamlines construction and information transfer. It makes the processes manageable and predictable. We hope that the users of buildings designed and implemented with the aid of digital methods will be able to experience a new kind of spatial expression, in which the careful and precise use of materials contributes to the impression of a pleasant whole. ↙