Panu Savolainen: In Finland, architecture has been considered more apolitical than it actually is

Architectural practitioners have traditionally promoted Finland's position as a Western nation, and this was not affected even by the left-wing movements of the 1960s and 1970s, claims Panu Savolainen, Professor in the history of architecture, in an interview with Daniele Belleri.

Can geology and geopolitics together tell us something about the future of architecture in Finland?

The climate crisis has forced us to rethink supposedly timeless elements of the Earth – air, oceans, and ancient sediments as not immutable or insulated from human impact, contrary to extractivist belief.

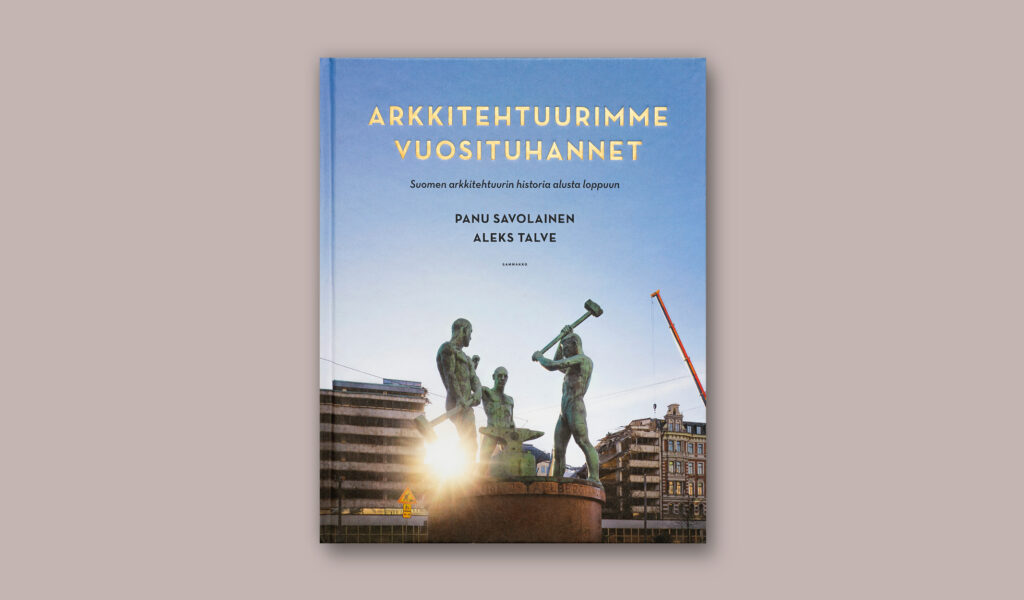

The challenge, as Dipesh Chakrabarty puts it, is shifting from a human-centred “global” mindset to a post-anthropocentric “planetary” one. This is one way to read the “geological turn” in history reflected in the 2024 book Arkkitehtuurimme vuosituhannet (“Millennia of Our Architecture”) by Panu Savolainen, Professor in the history of architecture and conservation at Aalto University.

Its subtitle promising to tell “Finnish architecture from the beginning to the end” sounds vaguely teleological. But is Savolainen really telling us that the history of architecture in Finland ascribes to some sort of higher, rational purpose? In fact, he is not. At closer read, it becomes apparent that that subheading owes more to a mischievous pun than to a historicist approach. Tracing Finnish architecture from its origins to a distant future, it concludes when a new ice age erases almost all human traces. That is the literal end.

In this frame, what is the role of geopolitics? Perhaps to remind us that while some nations cling to an old mindset – most starkly Vladimir Putin’s petro-imperial Russia – others may try to forge a new agenda. We might be doomed in the very long run. But before then, there is much to do and choose.

Finland, in fact, has consciously picked its camp. Did its agents of architecture, too?

Into the West through architecture

DANIELE BELLERI: I would like to start this conversation by going back to the origins of Finland as a nation. How was the geopolitics of architecture back then?

PANU SAVOLAINEN: It started when Finland was still a province of the Russian Empire, and architects tried to position the country as connected to the West. That was the original geopolitical mission of architecture in Finland.

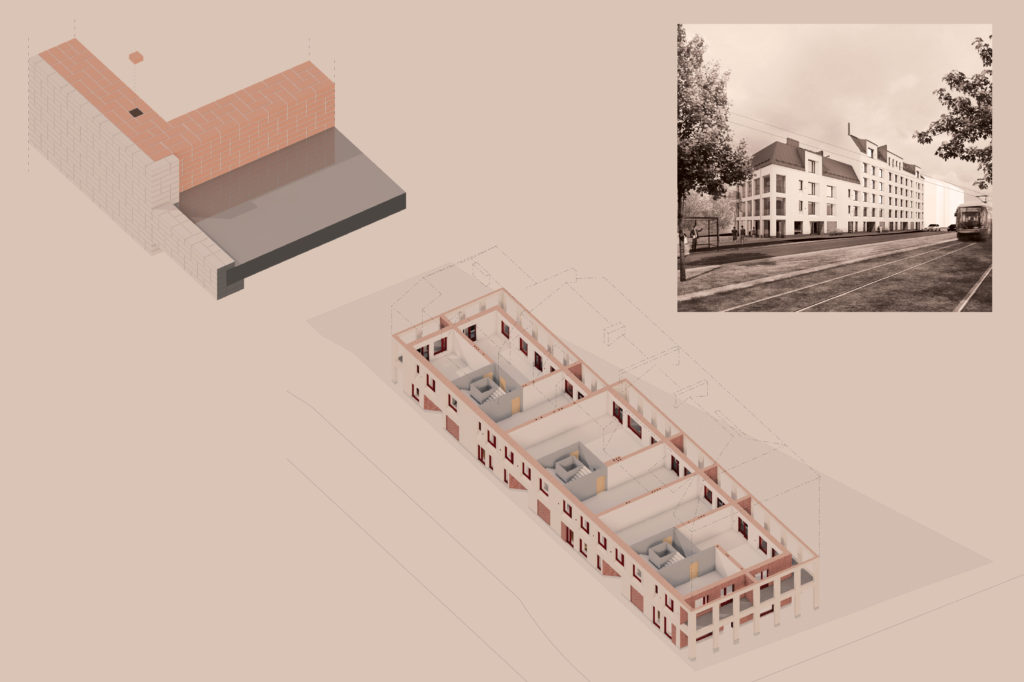

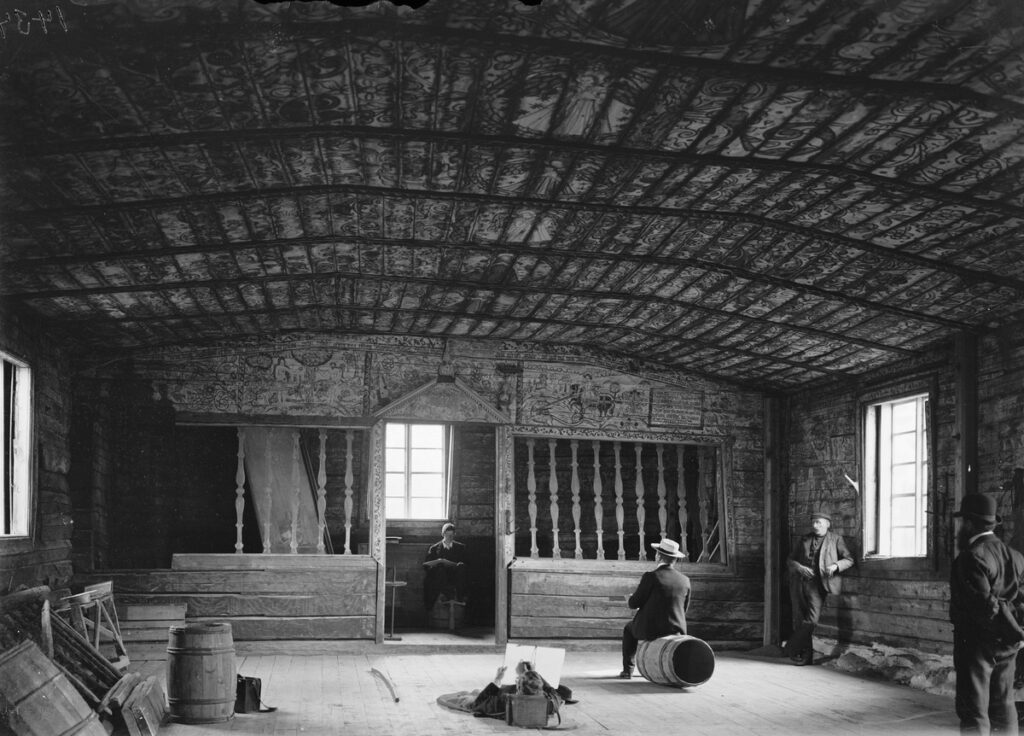

While architectural education was traditional, a central role in advancing a radical agenda was played by students. A group at the University of Helsinki and Helsinki Polytechnical School, most not yet graduated, established the Finnish Antiquarian Society in 1871, taking its model from Britain and France. They surveyed Finnish historical architecture, with the idea that churches or abandoned castles would be part of a heritage belonging to Western culture. They had a strong political purpose, even if it was not safe to pronounce it too loudly.

In this way, modern architecture morphed into a tool for nation-building. Think of the Finnish pavilion at the Paris Expo in 1900, Finnish romanticism with its patterns inspired by the Kalevala, or Aino and Alvar Aaltos’ work in the interwar period, caught between the modernist paradigm of CIAM and Jyväskylä as the “Florence of the North”.

DB: Fast-forward a few decades. Did the “new left” discourse of the 1960s and 1970s influence this geopolitical agenda, at a time when Finland was balancing between the West and avoiding confrontation with the USSR?

PS: Finland was almost left out of this internationalist left movement. Architects then were mainly concentrated on killing Alvar Aalto! Yes, in 1969 there was an occupation at the Department of Architecture in Helsinki, but that was it. If you try to find projects reacting to political discourse like elsewhere in Europe, it’s nearly impossible.

Once again, agents of architecture promoted Finland not only as a neutral country, but as a nation belonging to the West. Cultural organizations were crucial, as scholars like Petra Ćeferin have shown, for instance regarding the Museum of Finnish Architecture and its international exhibitions policy.

DB: So, for a century, the imperative was fostering a loose sense of “Western belonging”. Yet there was a reluctance to engage with any explicit political camp.

You are the first to pose this question about how the current geopolitical situation affects architecture.

PS: We have to go back to the Finnish political mindset for quietness, formed over decades or centuries of carefulness regarding Russia. Most likely, the tacit attitude of architects follows the general way of being neutral: to be quiet and not pronounce judgement, not even become conscious of judgement toward political reasoning.

In Finnish culture, architecture is thought less political than it really is. Even today, neutrality is still there. People do not want to talk about it. You are the first, in fact, to pose this question about how the current geopolitical situation affects architecture.

Strong attachment to the State

DB: Let me come back to practicing architects. You described them as more peripheral than cultural organizations or student associations in shaping the geopolitics of architecture.

One thing that is surprising to me is how some design offices in Finland rely on the State to run a substantial part of their business. There are major firms that focus heavily on open, anonymous competitions and spend far fewer resources on free-market-oriented business development, at least compared to other European countries. So there is a detachment from political engagement, yet a strong attachment to the State.

PS: Quite a lot, and with a long history. In 19th-century Finland, there were only a few architects and they were all in State offices. People like Carl Ludvig Engel, Carlo Bassi or Ernst Lohrmann had some private commissions, but they started very slowly. Only in the late 19th century did a strong culture of publicly built architecture and our competition system emerge: before private offices, in fact.

DB: So if the State chose new geopolitical priorities, the architectural scene would follow almost automatically, albeit perhaps not fully in a conscious way.

PS: Yes, precisely. And throughout history you can see that even though political awareness was not strong, architectural production was clearly politically led. Look at Senate Square in Helsinki: conceived as a portrait of imperial domination: a manifestation of Finland’s new capital belonging to the Russian Empire.

Finland outsources emissions

DB: Post-2022, do you see consequences on Finland’s architecture culture as the country took a strong geopolitical turn away from neutrality?

PS: It’s too early to say. But one practical effect is visible. It relates to wood for timber construction. We used to get good timber from Russia, but now that cannot happen. And we cannot build much with Finnish wood, because we don’t have enough timber. After WWII, we embraced a forest-industry model focused on cellulose, not slow-growing structural wood.

Finnish forest is not a forest. It is largely tree crop: 98.5% of it.

We cannot build much with Finnish wood, because we don’t have enough timber.

DB: Toward the end of your book , you explain how Finland outsources emissions and waste from construction to the Global South, and conclude with a rather harsh judgement: “Finland is a planetary parasite”. It’s a shocking statement about a country that often enjoys the reputation of being a sustainability beacon, for example through its 2035 decarbonization objective.

PS: Finland is good at promoting sustainability goals. But look at building-waste recycling: we are among the worst in the EU. There is a constant drive for new construction and demolition. We have one of the youngest building stocks in Europe, yet very high demolition rates, even for 25-year-old buildings.

DB: Where does that come from?

PS: Finland transformed from agrarian to industrial very fast. Many old people still remember living in rural log houses, then moving to modern suburbs. That felt luxurious. In the 1960s and ’70s, old objects and furniture linked to the agrarian past were discarded, even literally burned.

There is still a “shame of oldness”: if something looks used or imperfect, the instinct is to remove it. We do see counter-trends, but they are niche.

Alliance against climate change

DB: A final question on politics today. After Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Finland quickly agreed to enter NATO. Millions of people changed their long-held assumptions almost overnight. I recently discussed this with Sirkka Heinonen from the Finland Futures Research Centre, and she interprets this shift as a sign of Finland being a high-trust society, where information flows swiftly and decisions can be taken with broad agreement.

I suspect this hopeful reading might underestimate the increasing complexity of a less homogenous society. Yet even when discussing climate change, it is true that you perceive less polarisation than in other parts of Europe. I am curious what you think of the theory of French philosopher Pierre Charbonnier. He categorises “three tribes” of political ecology – “radical critics of modernity”, “green socialism” and “elite technocracy” – and argues that an alliance between these camps is necessary.

That idea was central to my work at the Venice Architecture Biennale 2025. Is this alliance already under way in Finland? Could the fight against climate change become a “safe corollary” of the country’s new geopolitics, not least because Russia is such a strong climate-change denialist?

We have one of the youngest building stocks in Europe, yet very high demolition rates, even for 25-year-old buildings.

PS: It’s an interesting hypothesis. I have been working on a similar system of political categories with my students. I see that all political parties in Finland, except the anti-system Finns party, probably subscribe to at least one of these “tribes”. Kokoomus, the centre-right party of Prime Minister Petteri Orpo, embraces the third tribe’s techno-solutionist approach with market tools. The left, either the Green Party or the Left Alliance, oscillates between the first tribe’s critique of human hegemony over nature and the second tribe’s focus on social equality.

And then there are ambiguities in the heritage of figures such as the eco-fascist Pentti Linkola, which contributed to the birth of environmentalism in this country, or in ideas of radical indigenous simplicity and living with much less. In short, these categories are evenly distributed in Finland’s politics of climate change.

DB: And beyond politics, how do you see the situation in architectural culture? Which of the three tribes is hegemonic? I am curious to understand whether the focus on communications technology in the economy of this country over the last few decades created any ripple effect in architecture.

PS: In architecture culture, whether academia or practitioners, the situation is quite different. What you see is that the “radical critics of modernity” and “green socialism”, to borrow Charbonnier’s terms, are clearly hegemonic over computational-oriented design visions.

The interview is the second part of the series “Finnish architecture in the shadow of geopolitics”, which will be published on the Finnish Architecture Review website during the winter of 2025–2026.