Pilvi Kalhama: “Today’s construction culture is too cautious”

Finland spends too much time calculating risks, says Pilvi Kalhama, director of the Museum of Architecture and Design. This may also be the reason why no major Finnish companies have emerged in the creative industries in recent decades, Kalhama says in an interview with Daniele Belleri.

When Pilvi Kalhama took over as director of Finland’s new Museum of Architecture and Design in August 2025, her first public statement struck an unusual chord in the understated Finnish design scene. It sounded a bold note of ambition. “The new museum will rise to meet global expectations. Not only in content and design, but in its civic mission.”

How will Kalhama help the organization get there? Her institutional playbook – refined over two decades at the helm of both private and public art institutions in Finland – might provide a hint of what’s to come. Kalhama is one of the founders of the Helsinki Contemporary art gallery and served as the director of EMMA – Espoo Museum of Modern Art from 2012 to 2025.

Kalhama has shown a keen interest in pursuing experimental collaborations with public and private partners, as well as an ability to mount exhibitions that engage broad audiences without sacrificing academic rigour. She does not see the museum as a solo protagonist, but rather as an aggregator of energy and collective confidence.

It’s a promising formula, which proved successful in boosting the international reputation of both Helsinki Contemporary, and EMMA. The question is whether that recipe will be enough to lead an architecture and design sector at a crossroads, and whether Kalhama can turn her ambition into a wider movement that overcomes the industry’s aversion to risk. The selection of Carson Chan, former director of the Emilio Ambasz Institute at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, as the museum’s Chief Curator, points toward a strong international shift.

When this conversation happened in late September 2025, when the museum’s winning design had just been announced. That process, which began long before Kalhama’s appointment, had drawn public criticism in Finland. Still, the director defended the outcome, insisting on the essential connection between the JKMM-designed future building on Helsinki’s south harbour, and the reach of the institution’s ongoing cultural program.

As the conversation moves forward, matters of cultural vision intersect with the psychological undercurrents of the Finnish mindset – a mix of ambition tempered by restraint, and of compromise shaped by caution. The success of Finland’s most progressive museum project in decades may depend on how well it navigates these opposing impulses.

Since the establishment of the Museum of Architecture in the post-war years, this organization has often played a crucial role in position Finland in the international design discourse, acting as a de-facto geopolitical actor. How will Kalhama engage with this history and contribute to its new chapter?

Too cautious

DANIELE BELLERI: Let me quote a passage from your introductory statement: “Design and architecture have always reflected society’s values. We need a museum that elevates these fields as tools for justice, empathy, and transformation.” What kind of transformation do you hope to achieve, especially in this time of geopolitical upheaval?

PILVI KALHAMA: We’re living through deep uncertainty, and it will continue. But at a time when the world’s eyes are on Finland, the only way forward is to take a clear stance. On the one hand, that means developing deeper cooperation with our neighbours in the Nordic-Baltic region, now that we’ve all awakened to the same threats Finland has long felt.

It does not make sense to just talk about beautiful objects from the past.

On the other hand, it’s about taking risks. And that’s our real challenge. Finnish society has become reluctant to take risks, something we don’t discuss enough. As a museum, we can push creativity and innovation. Without risk, we fail the future.

DB: What are the effects of this risk aversion?

PK: We spend too much time calculating risks and then move too safely. Maybe that’s why no major Finnish companies have emerged in the creative industries in recent decades. Even our biggest architecture firms are one-fifth the size of those in other Nordic countries.

DB: Can a museum counter this in any way?

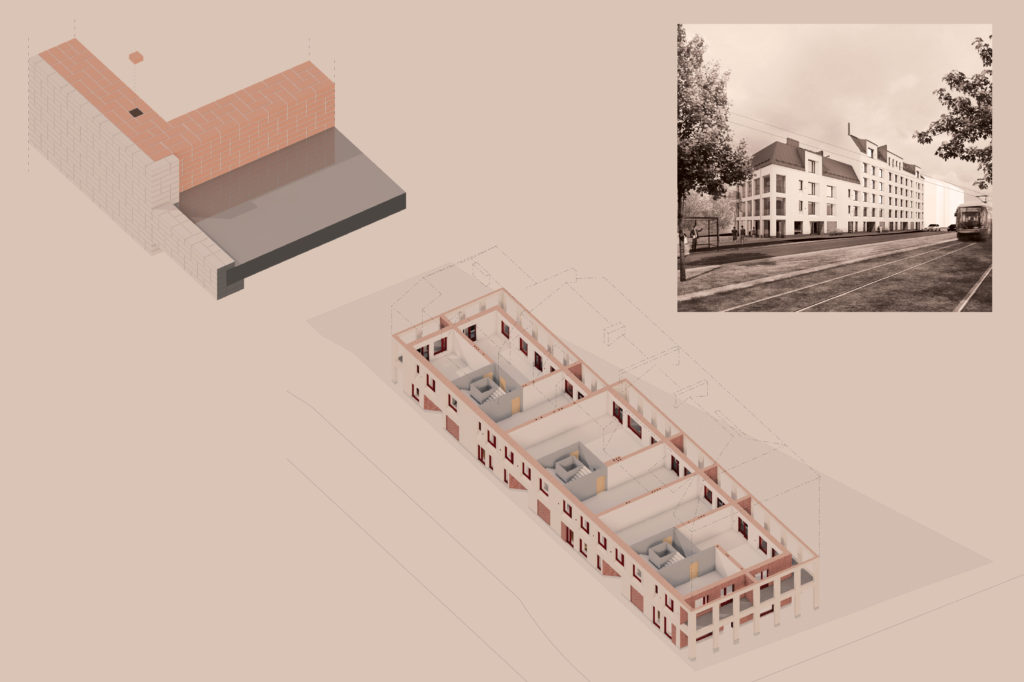

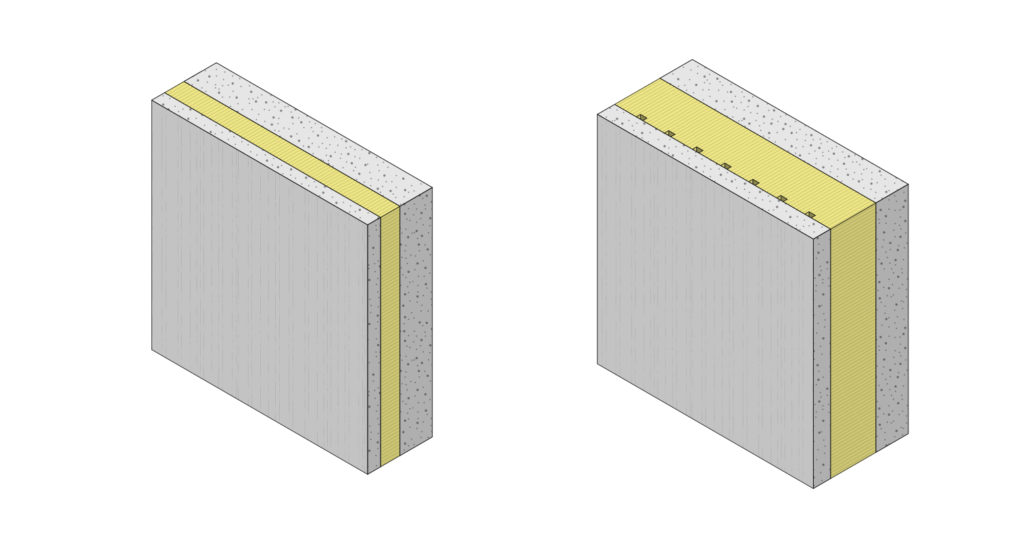

PK: It can set an example of ambition. Our building competition shows that: it’s advancing the harbour’s renewal and redefining Helsinki’s maritime identity. We’re also testing new sustainable construction methods, creating a pilot for future public and even private buildings. Today’s construction culture is too cautious, driven by short-term economic considerations.

DB: Beyond the building, how do you hope the museum’s programming can shape the future?

PK: It’s part of who we are. I mentioned uncertainty earlier. Well, museums, along with libraries and schools, can help maintain a sense of stability in society and gather together so they can participate and act together. In the Nordics, these institutions are built for permanence, for activity ten or even fifty years ahead. They should keep evolving, but they also embody continuity, which is something rare in today’s world.

Outdated hero narrative

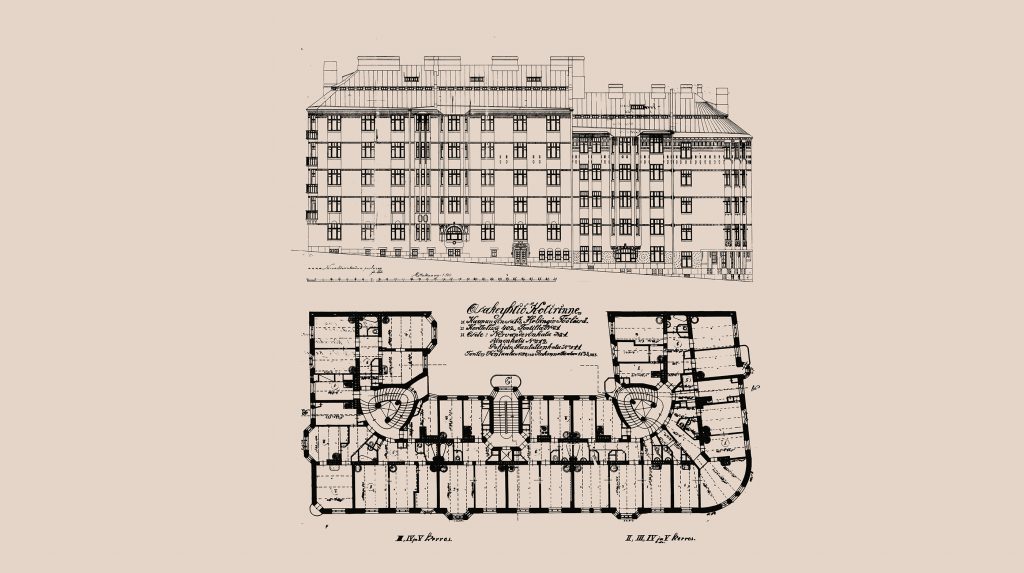

DB: In 2026, it will be seventy years since the Museum of Architecture was founded. Is there something that can be learned from that time?

PK: If the great story of Finnish design was written in the 1950s and 1960s, we can write a new one now. Back then, the geopolitical situation was difficult, yet there were still some certainties. Today we don’t have those, so we need to believe in ourselves and develop new strategies and new understandings on how we identify ourselves today. The museum should be a generator of energy for society, countering the current rhetoric of cuts and limitations, and turning it toward possibilities.

DB: And what instead should be discarded or opposed from a certain cult of the past?

We should acknowledge those works that responded to civic action rather than individual heroism.

PK: Our design heritage is fantastic and gives us international credibility, but those names and stories that we all know are often too static. We need to reexamine them. We need to finally challenge the “hero narrative” of architecture and design in Finland. The museum can play a key role in that process. It does not make sense to just talk about beautiful objects from the past.

We need the confidence to move forward with new eyes. Architecture and design history should open to new narratives. For instance, we should acknowledge those works that responded to civic action rather than individual heroism, and ask what we can learn from that for our future.

Against accepting the average

DB: What buildings in Finnish architecture history have a primacy in illuminating the possibility of a better future?

PK: I would cite two of them: one is Raili and Reima Pietilä’s Dipoli in Espoo. A signature building whose use is still very alive, ever-changing. It fits beautifully into nature but also presents us with ideas of innovation in future uses.

And going even further back, thinking about Finland as a rural country: we should better acknowledge the importance of timber houses and vernacular architecture. These buildings breathe. They embody healthy qualities for our future.

DB: When I started working on the Biennale Architettura in late 2023, we received this piece of advice from Paola Antonelli, the Senior Curator of Architecture and Design at MoMA: think about what you want your exhibition to be against. So, to conclude on a contrarian note – what do you wish to be against?

PK: Against the idea of accepting the average. Those situations where the ambition to create a better world ends in compromise. Compromise, at the moment, is the biggest mistake our fields can make.

What we do must be done with enough ambition.

No compromising, for example, when it comes to sustainability. Or when it comes to creating a healthy environment – no compromising because of finances. Let’s not build those buildings then. What we do must be done with enough ambition.

And that counts for the museum as well – if we don’t have the resources to do something properly, then we wait. What we do, we must stand for 100%.

The interview is the third part of the series “Finnish architecture in the shadow of geopolitics”, which will be published on the Finnish Architecture Review website during the winter of 2025–2026.