Published in 2/2017 - schools, female architects

Architect, Entrepreneur, Woman

More than half of architectural students are women these days. Yet the number of private architectural offices run by women is surprisingly low. Four architects discuss their work and ideals.

A female architect as a concept is misleading in that it groups together a widely diverse set of architects, whose design methods and architectural expression can sometimes be quite different. My guests, too, represent diverse career paths. Is it possible to find a particular reason for women seldom being leaders of private practices? One way to end up establishing an architecture practice is to succeed in an architectural competition. Could this be the answer?

I’ve seen how draining the competition process is, and it does not seem to me a rewarding way to live.

Pia Ilonen

The Joys and Restraints of Competitions

The usual reason given for the absence of women in architectural competitions is that women are not competitive. Kirsti Sivén is living proof of the exact opposite: “I have always loved competitions. I’m driven by difficulties and challenges.” Pia Ilonen admits that she has no competitive instinct, which is why she has made a conscious decision not to participate in competitions: “I have seen, as the daughter of two architects and as an assistant, how draining the competition process is, and it does not seem to me a rewarding way to live, especially as a single parent. I develop design tasks myself. They have to feel significant to me and to be on my own terms. Don’t get me wrong: I face plenty of challenges and difficulties. Rescuing the Cable Factory in Helsinki for cultural use in the early stages of my career was one result of such a process.”

Jenni Reuter is Professor of Architectural Principles and Theory at Aalto University. She also works at Hollmén Reuter Sandman Architects, which was established in 1996, and for Ukumbi, a non-governmental organization offering architectural services to communities in need around the world. She also runs her own architectural office established in 1999.

Jenni Reuter is also known for creating her own projects: “The same amount of time I would spend on competitions, I can spend on developing my own projects. Both approaches are valid. They take architecture forward and create something new.” Miia-Liina Tommila points out that several women-led offices have been established in recent years and have also succeeded in competitions.

In competitions, it is important to be able to simplify and conceptualise one’s ideas, which means that many issues can be left unresolved. Women are often interested in solving functional issues and are good at handling multiple challenges at once. Could it be that this type of expertise doesn’t sit well with current architectural competitions? “I don’t see any difference in architecture created by men or women, but maybe there is a difference in how men and women approach the design task. Do women spend more time from the beginning on the functional issues, while men work with form first?” Ilonen ponders.

Kirsti Sivén is a partner at Kirsti Sivén & Asko Takala Architects. The office was established in 1983 as Kirsti Sivén Architects. She is known particularly as a housing architect.

Sivén describes her own work method: “My approach varies. If I design for a competition, I need to simplify and think about my priorities. You have to learn to fade out irrelevant aspects that will have to remain unresolved in the entry. I don’t know if women in general are more diligent in this respect, but with us it is the other way around. My business partner Asko [Takala] usually drags me back to earth and he reminds me if I’m overlooking building services and other practical things like that in our competition entry. This is also a matter of learning. You get better at whatever it is you practice.”

As young trainees, women often end up taking care of tasks that require meticulous care, while men want to be part of competition teams. “Women might think that if they carry out the routine tasks well enough, they will eventually be rewarded with more interesting jobs. It is possible that men are better at asking for more,” Reuter says. It is also impossible to say whether male dominance in competitions is a sign of women’s poor success or just that women don’t participate in the first place.

Would you choose security or risk?

Entering competitions and running a business take courage. You expose yourself to judgment, risking failure and financial insecurity. “Could it be that women are generally more security-driven than men?” Tommila asks. Reuter replies: “Girls are not encouraged at school to take risks, even if it means you fail. Girls are expected to be diligent from early on, and this is a trait that gets stronger at the expense of other qualities.” She says that as a professor at Aalto University, her educational goal is to encourage students to take risks. “Architecture is all about risk and experimenting.

Girls are not encouraged at school to take risks.

Jenni Reuter

Playing safe never results in anything new or interesting.” Ilonen remembers how she worked in a mainly female work space in the early days of her career. When the time came to set up a limited company, only one of the young women was ready to join her venture as a partner. The rest started thinking what would make sense financially and what would happen if things didn’t go according to plan. “I think we are on point in this,” Tommila says.

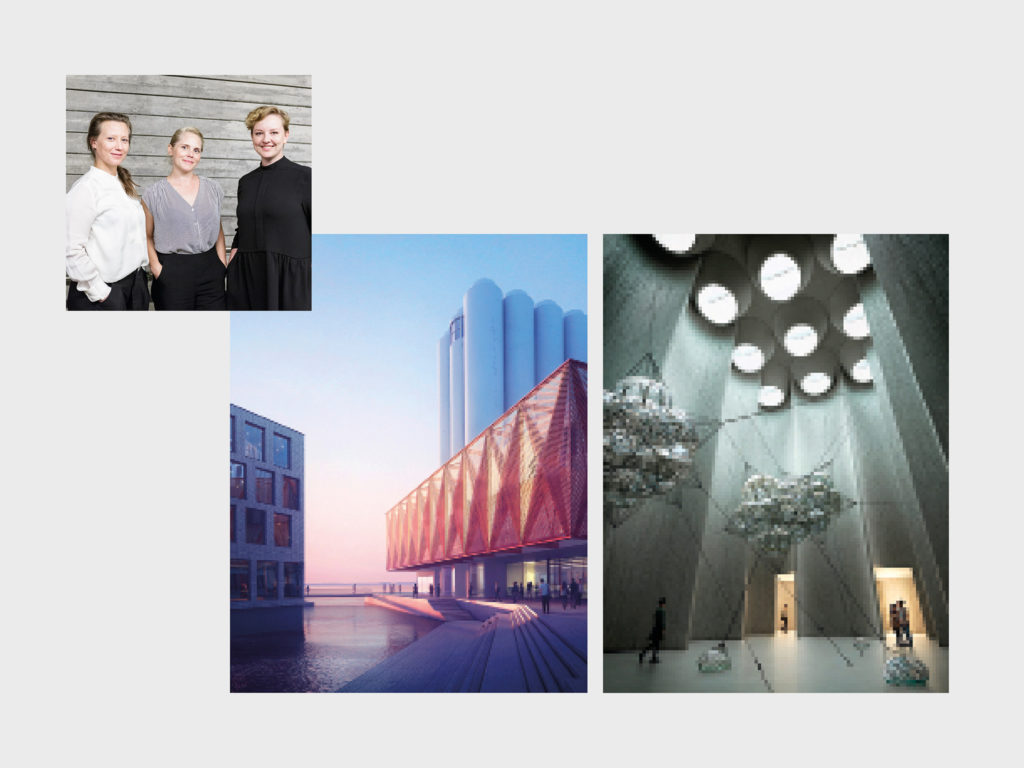

Pia Ilonen is a partner at Talli Architects, established in 1995. She is a strong advocate of inclusive projects and an active contributor in public discussions. She has designed restorations of high-profile cultural buildings and housing. (Second from the right in the photo)

Women are security-conscious maybe because they still often take the main responsibility for children in the family, for example. A female entrepreneur will find it difficult to take maternity leave, because leadership cannot be delegated to someone else. As employees, women are a potential risk for the employer, which may affect women’s employment opportunities. “The parental leave of employees is quite a burden for the employer. Equality in the working world can only be achieved if the costs of parental leaves are covered by taxes, and the only thing left for the employer to worry about is the recruitment of the substitute,” Sivén says. Ilonen agrees: “We have always encouraged our employees to have babies, but the fact remains that they do make a dent in a company’s finances.” If the costs of parental leave were more evenly distributed, women would be mentally freer to make their own choices. This would probably also soften the attitudes towards women’s role in the workplace.

Women are often asked about the difficulty of combining their career and family. Similarly, men who take more responsibility for the home than women are also treated as oddities. Reuter tells a story of how her architect husband was asked if he was babysitting for the evenings when his professor wife was at work. Her husband had merely replied that he is the father of the children and that he acted accordingly.

Women come across similar skewed attitudes at work. It shows in the assumptions that women design mainly kitchens and interiors. Ilonen says that in reality this is not the case, and in her office most of the architects are women and most of the interior designers are men. The myth of a nurturing instinct is deep-seated and it is something that female leaders constantly have to face: “Women are expected to be maternal and lenient, but these are qualities that seldom go hand in hand with leadership. The contrast between expectations and the reality is too much for some. When a male leader speaks his mind, he is seen as a strong leader. When a woman does the same, she is seen as a mean bitch,” Sivén says.

Ilonen thinks these expectations of softness come partly from women themselves. She describes how worried she once was after speaking quite sternly at a meeting, thinking she may have been too harsh. “How typical of a woman!” Women, however, are different in this respect, too. “If I know that a certain thing needs to be done in a certain way, it is better to say so there and then rather than risk a much bigger grief when you have to reject something that the person has worked on for a long time,” Sivén says.

The importance of role models

Another thing women are not encouraged to do is to talk about their own achievements. Are girls brought up to be content with a good result and not want personal glory for it? “For me, the most important thing is to work on great projects, and a good result is the best reward. Publicity is nice but not a goal of any kind,” Reuter says. Sivén hastens to add: “I don’t see participation in competitions as hankering for glory. I want to work in this field because I have the need to create something complete in this world and in this field the best way to achieve that is through competitions.”

I want to work in this field because I have the need to create something complete in this world.

Kirsti Sivén

Tommila ponders about the star culture in architecture and how individual architects are raised above the rest of the team: “Architecture is something that happens as a result of the work of extensive networks and teams. It seems so old-fashioned to glorify one person, when this usually means depriving someone else of their due credit. I feel I’m at my best as part of a team. Collaborative skills are difficult to brand, but they are absolutely crucial skills and they show in the way the new generation works.” Sivén illustrates her point: “I would compare architecture to film making: both have a large team of professionals, who all need to know what they are doing and deliver, but in both arts, it is the director who makes the big decisions.”

Miia-Liina Tommila studied architecture in Bergen, Norway. She is a partner in Kaleidoscope Architects, an office established in 2013 that engages in inclusive urban planning in Uusi Kaupunki, “New Urban Collective”. Tommila also works as a project architect. (On the right in the photo)

The lack of role models is a self-feeding cycle and narrows down the scope of opportunities. “Role models are not a necessity, but when you are young, you may not be able to see all the possibilities open to you, if nobody has ever told you about all the things you could do,” Reuter says. Tommila adds: “The designers who have been significant to my development as an architect have all been women. I don’t know if I’ve specifically sought out women, or whether it has been just a coincidence, but for example architect Sarah Wigglesworth, who supervised my Master’s degree studies, and my employer Merete Lind Mikkelsen in Denmark have had an immense impact on my architectural thinking.”

Ilonen jumps in: “The talk by Grafton Architects at the Museum of Finnish Architecture was incredibly inspiring! I went straight home from the lecture and solved a design problem I have been stuck with for ages! That shows the power of role models!” Reuter adds: “I’m really happy that they are the next curators of the Venice Biennale. It is important that such visible roles are also held by women. No matter how much you’d like to think that publicity doesn’t matter to you or doesn’t define the value of your work, it is important to architecture itself and inspiring to colleagues. Seeing great projects and architects at work is inspiring to all. It is our duty to stand up and stand out and talk about our architecture and how we make it.”↙

ELINA KOIVISTO (b. 1985), architect SAFA (MSc), Helsinki. Entrepreneur, teacher, project architect, activist. Believes in the power of architecture to create a better world.